(originally published in Negative Print Fanzine, September 1983)

Part One.

As far as most of us are concerned, the musical apocalypse happened in 1977 with the Sex Pistols in England, opening the door for new forms of rock’n’roll. Yeah, we all know the Dead Boys released their first LP that year, but the members didn’t suddenly appear overnight. Clevo does have a past – most of the participants in this early subculture are still around. Jim Jones and Brian Sands who both work at Record Rendezvous at 3d and Prospect were part of it; so was Tony Maimone, who now has a band called Tight Dreams; Nick Stephanoff is now Nick Knox of the Cramps; and the legendary Peter Laughner tragically ended up dead of natural causes in 1977. I can’t begin to chronicle those days in very much detail – I was a minor myself back in those days. I can, however, try to give the reader a feel for the Clevo underground of 1967 – 1979, a glimpse into the musical roots of our industrial city.

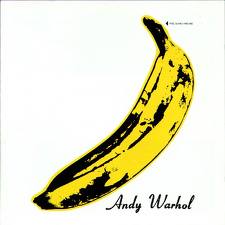

People who complain about the situation now don’t realize that in 1971, having a regular place to play and hear original music (besides garages) was beyond the wildest dreams of those involved. The closest thing to a underground bar was La Cave on Euclid Avenue near E. 103d near CWRU, where the Velvet Underground held court as the house band from ’67 to ’69. This is where Peter Laughner and other Clevo bands of the time got their strong Velvets influence.

Peter was one of the driving forces of the Clevo scene in the early ‘70s, being both journalist and musician. Laughner’s first band, Mr. Charlie, was born when he was in high school; he went on the join the Mr. Stress Blues Band as one of their more interesting guitarists. He once met Lester Bangs, rock writer extraordinaire from Creem Magazine, which led to the publication of several Laughner articles in that beloved rag. Laughner’s next band, Cinderella Backstreet, was formed in late 1972 and included Albert Dennis, Rick Kallister, and Scott Krause (later drummer for Pere Ubu and Home and Garden.) CB played the Viking Saloon on Wednesday nights in the early 70s; the Viking was a CSU bar at 2005 Chester which burned down in late 1975. Laughner was heavily into the Velvets and Stooges at this time and had actually put an ad in the Plain Dealer asking for some “real punks”. The two guys who answered, Johnny Madanski and Gene O’Conner will be featured in Part Two of this article.

Around the same time Laughner was playing in Mr. Charlie, his good friends Craig Bell, Jamie Klimek, Jim Crook, Mike Weldon and Paul Marotta formed the “quintessential basement band”, Mirrors, while attending Lakewood High. Mirrors was heavily Velvets-oriented too, Craig and Jamie having spend many nights sneaking into La Cave with Peter. The band sang of “lust and degradation”, but seldom left their basement except to play several Lakewood YMCA teen dances. When Craig Bell was drafted, Jim Jones replaced him on bass. The band stayed together long enough to finally release a single in 1977, “She Smiled Wild” b/w “Jailbait” and ”Shirley” (recorded in 1975) on Hearthan Records (Pere Ubu’s label.) A few of the Mirrors then formed the Styrene Money Band, which still did the Mirrors’ “Cheap and Vulgar” and released a fairly well-known single, “Drano in Your Veins” around 1978 or so.

Probably the most infamous of the early Clevo underground bands was the Electric Eels, featuring Dave McManus on lead vocals, clarinet and lawnmower; John Morton as guitarist and tinfoil head; Paul Marotta, Brian McMahon and itinerate drummer Denny Foland, Nick Stephanoff and Tony Fier made up the rest of the band. Nick went on to fame and fortune in the Cramps, replacing another Ohio resident, Miriam Linna, who formed the Zantees. Tony Fier started the Styrene Money band with Paul, and John Morton had a non-band of the visual arts, Johnny and the Dicks. Some of the Eels originals were “Safety Week”, “You’re Full of Shit”, and “Flapping Jets”. They did several non-originals too – The Patty Duke theme, Lawson’s Big-O commercial, the Flintstones theme and Dead Man’s Curve.

The Eels hardly ever played out either, but posthumously released a single in 1979 which has had some influence in today’s scene – “Cyclotron” b/w “Agitated” (I’m positive this is where the Plague got their best tune!) The Eels biggest gig was also the most legendary of the Clevo underground scene of the time – “Special Extermination Music Night” with the Eels, Mirrors, and Rocket from the Tombs (more about them in Part Two.) The poster proclaimed “Attendance Required” and the venue – the Viking Saloon on December 22, 1975, with – are you ready for this? – Kid Leo as the HOST! This gig went over so well that the Viking couldn’t top it, and spontaneously burned to the ground the very next day.

Part Two.

In the opening years of the seventies, David Thomas, a teenage heavy metal freak, badgered Scene editor Jim Girard until he let him write a column. This column transformed David into “Crocus Behemoth” in 1971, by 1972 it was “The Phlorescent Crocus and Ricky”, then in 1973 “Croc ‘O’ Bush” (with Mark Kmetzko.) Local band and scene news showed through the Crocus column for years, and it made David something of a Clevo celebrity, but nothing compared to his notoriety in his later bands.

It must be remembered that WMMS was not the enemy back in 73 or 74; they were an underground radio station at that time, where no tune was ever played twice in one day (well, almost no tune.) The Scene and WMMS bunch were known as the “Cleveland Mafia” (more appropriately now, but then merely as a joke) and had a joke band called “The Great Bow-Wah Death Band”, with Davis Thomas as “Dr. Science”. It could be described as “free-form anarchy”, included a few genuine musicians, and played at the Viking Saloon, Agora and the glorious House of Bud (now a parking lot across from CSU.)

David really wanted a more musically proficient band to “bring Cleveland to its knees”; his favorite bands were the Stooges, MC5, Blue Oyster Cult, Lou Reed, and the Youngstown glitter/metal band Left End. On June 14, 1974, he made his debut with the now-legendary Rocket from the Tombs, originally also including Kim Zonneville (a/k/a Charlie Weiner), Tom Clements and Glenn Hach, at the Viking Saloon. David described the band at first as a “punk rock lampoon” and a “New York Dolls takeoff” – they even did a version of Zappa’s “Flower Punk” called “Hey Punk” as well as other assorted zaniness. In October 1974, Peter Cangliner joint Rocket from the Tombs, and Charlie Weiner left when David and Peter wanted a more “serious” band to do Stooges-type material.

In early 1975, Gene O’Connor and Johnny Madansky, the two “real punks” who had answered Peter’s 1971 P.D. ad joined Rocket from the Tombs. They had previously been in a band called Slash, doing N.Y. Dolls, Kiss, and Mott the Hoople covers. These two were also Stooges fans, and R from the T now did “Raw Power”, “Search & Destroy”, and “Rich Bitch”, which didn’t come out until 1976 on Metallic KO, but was performed by the Ig in Clevo (opening for Slade) at the Allen Theater in February 1974. Original Rocket from the Tombs tunes included “30 Seconds Over Tokyo”, “I Heard Her Call My Name”, “Life Stinks”, “Sonic Reducer”, and “Down In Flames” (last two made famous by the Dead Boys.) The final addition to Rocket from the Tombs (in May 1975) was Stiv Bators from Girard, Ohio who was an Ig fan and local scenemaker. In 1970, NBC filmed the Stooges in Cincinnati for their “Experiments in TV” show, and as Iggy was walking on the hands of the fans into the audience (first stage diver?) Stiv handed him a jar of peanut butter which he spread on his chest. This incident made Stiv famous nationwide, it being a network show.[1]

In early 1975, David and Peter badgered Kid Leo so much that he consented to having Rocket from the Tombs on his Sunday night interview show on ‘MMS. Rocket even got to play the Agora in May of 1975 after Stiv joined. Before this though, Peter arranged to have Television play Clevo at the Piccadilly Inn at E. 30th & Euclid (in the Penthouse.) He financed the gig out of his own pocket; it was TV’s first non-Manhattan gig, and Rocket from the Tombs was the opening act. At this time Kid Leo and others at ‘MMS were playing Television’s first independent single pretty heavily, a version of Roky Erikson’s “Fire Engine” from the Eno demos.

After the Television show, Peter Laughner left Rocket from the Tombs to play in the (Television inspired) band Friction. Friction had as a member Adele Bertei, who later was in Peter and the Wolves with Laughner, and then went to N.Y. to join James Chance and the Contortions. This left only David Thomas, Stiv Bators, Gene O’Connor, and Johnny Madansky in Rocket from the Tombs. With too few places to play (RFTT once played Bain Park Community Cabin in Fairview Park for a teen dance) and too diverse ideas, Rocket split into Frankenstein (including Stiv, Johnny and Gene) and Pere Ubu which David formed with some ex-Cinderella Backstreet members. Frankenstein was more of a true punk band. On New Year’s Eve 1975 they played the Piccadilly Penthouse and engaged in a little pool cue-swinging, making then notorious toughs immediately. In late 76 and early 77 they played the Crypt in Akron, run by the guys in the Rubber City Rebels. Pere Ubu, of course, went on to become the most famous and well respected Clevo band so far, touring Europe many times and putting out numerous singles, albums and EPs between 1975 and 1981 when they broke up. David planned Ubu to be more of a psychedelic, Seeds-influenced band, but it went far beyond his wildest dreams to become one of the most intense and unique bands ever heard. Even back in 75-76 WMMS was cool enough to play Ubu’s legendary tunes, “30 Seconds Over Tokyo” and “Final Solution” before they went totally corporate. Pere Ubu was also the first non-Manhattan band to play Max’s Kansas City in New York, and in fact was included on their compilation album in 1976.

Frankenstein was a band with a shaky foundation, and split up soon after forming. They must have had some conflict, because Gene O’Connor (now Cheetah Chrome) and Stiv Bators answered an ad in the musicians section of Scene advertising for members to complete a hardcore band. This was in early June of 1976. My brother and his guitarist put the ad in to find a singer and bass player, and talked to Cheetah for close to an hour on the phone about the band Cheetah was forming. Unfortunately my brother’s guitarist had a broken finger and couldn’t play for a month, so even though addresses and phone numbers were exchanged, Cheetah and Stiv couldn’t wait. They packed up and went to N.Y., taking their old drummer Johnny Madansky (now Johnny Blitz), adding Jimmy Zero on 2d guitar, and leaving the bass section flexible (like Roxy Music did.) About a month after the phone call from Cheetah, a picture and note in the Scene announced the new Clevo band in New York – “The Dead Boys”. The Dead Boys played their first near-Clevo gig at Chippewa Lake Park at a concert put on by WKDD-FM, Akron (now soft rock.) Other bands there were the Rubber City Rebels, Blue Ash (from Youngstown), and Mahogany Rush who gave out the lyrics to their “World Anthem” so people could sing along. The next Clevo gig was a bit closer, in Lakewood at the Phantasy – Channel 8 News even showed up and made the Dead Boys go on early to get a few live shots for the 11:00 news.

Rocket from the Tombs tunes showed up on the first two Dead Boys albums – “Sonic Reducer” and “Down In Flames” on the first one, and Peter Laughner’s “Ain’t It Fun” on the second, with a recording of Peter’s voice at the end saying “I’m dead”. Stiv Bators claims that the Dead Boys are haunted by Peter.

Part Three.

The Summer of Love, 1967, saw a band called the Munx get started around town. The band included Bob Bensick (who returned around 1982 with his wife in an MTV-style band called Berlin, now Zara), Denny & Billy Earnest (who just may have later become Deadly Earnest and the Honky Tonk Heroes, – not being a Country/Western music fan, I can’t say for sure.) In 1969, Bensick formed Sheffield Rush (many bands had “Rush” in their names back then, before the Canadian Rush. Who out there remembers Joel Lariccia’s “Roseflown Rush”? I guess everyone was “rushing out” in those days!) That last year of the 60s brought us probably the most legendary original band to come out that early in Clevo. Moses included not only two ex-Choir members, Randy Klawon on lead guitar and Dennis Carlton on bass, but also David Alexy on drums and our own Brian Sands (a/k/a Brian Kinchy) on vocals and guitar. Moses played the legendary Midwest teen club circuit located in shopping centers and obscure suburbs (remember Cyrus Erie West, formerly a Hullaballo, in North Ridgeville?) throughout Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania. They opened for the Stooges several times, at the Chagrin Armory and Mentor Hullaballoo, and also for Alice Cooper twice (once at the N. Ridgeville Hullaballoo in 1971.) They did an original song called “Shock Treatment” six years before the Ramones hit the big time, as well as many other tunes they had written – this was the heyday of cover bands, remember. They also gave out illustrated programs and sometimes even wore masks – again, years before other Clevo “theatrical” bands such as Fayrewether and Molkie Cole tried these techniques.

The early 70s brought out the same bunch with new bands – Bob Bensick form and electronic band with Allen Ravenstine called “Hy Maya” that used to give “performances” from time to time, mainly on the East Side. David Alexy and Dennis Carlton from Moses formed a band called “Milk” in 1973, which also included Al Globekar, later to be in Circus. They were also theatrical (wasn’t everyone back in the glitter days?), played Cyrus Erie, and once opened for Canned Heat. Ex-Moses Brian Sands played around with several projects, Brian Bulldog (toy drum kit, pre-recorded tapes) and Brian and the Juniors (with two 15 year olds, circa 1978.) Brian also did the fab 60s commercials at Disastrodome II at the WHK Auditorium in 1978 – Farrah Fawcett for Dubonnet, and the infamous Doral “Taste Me, Taste Me” spot. One can converse with the legendary Mr. Sands at Record Rendezvous at 3d and Prospect downtown, or read about him in the “S” issue of “CP” Magazine.

The “Summer of Hate”, 1977, didn’t pass Clevo by as far as punk bands go – a slew of ideas were flying around town at that time. Probably the major punk entrepreneur of this period was Johnny Dromette, who owned the Drome record store. He used to have bands play in the window of the store up on Cedar Hill near Coventry – Devo was one of them, the Pagans were another (see the cover of their single “What’s This Shit Called Love?” for a memorialization of the event.) Dromette also managed the Pagans, who did their first gig July 6th, 1977 at the Looking Glass in Euclid. Even then they did a fair amount of covers, including “(I’m Not Your) Stepping Stone” and even (ugh) Rolling Stones songs; Mike Hudson, Tom Metoff, Tim Alee and Brian Morgan were in the band then, and their first single (still considered by some to be their best offering) was “Six and Change” recorded live in October 1977.

Cle Magazine was the premier publication at the time though only four issues came out (all collector’s items now.) Contributors and staff included David Thomas, Johnny Dromette, Mike Weldon, Charlotte Pressler, Mike Hudson, Andre Klimek, Mark Mothersbaugh (as artist) and John Morton, (a/k/a Johnny and the Dicks visual art band.) Cle number 3A had a 2 page rundown of all Clevo alternative bands, and it is a revealing bunch of history to say the least! Some of the bands mentioned were: The Baloney Heads, featuring ex-Bluestone Drummer Wally Gunn and ex-Strutter drummer Jeff Cougenour; Live Jack, a nine year old from South Euclid who sent Cle tapes with a heavy Stooges influence, featuring songs such as “School’s So Dumb”, “People Growing Beards” and “Microscopic Jets”; and a young 3-piece called Public Enemy with a tune called “New High School” and the fastest ever version attempted of “I Wanna Be Your Dog”. Also featured were the Dromones, which Johnny Dromette formed to be “a crass, one-gimmick exploitation of modern trends”; they did 30-second tunes like “Coed Jail”, “Drome Theme”, “5 Seconds over Borneo” and an extremely condensed “Master of the Universe” by Hawkwind. They opened for the Pagans and others, and were all Drome employees – Mike Weldon (ex-Mirrors), Jim Ellis, and Pasadena Dromona as chanteuse. Ex Blank X was another clever band with ex-Eels members doing ex-Eels tunes, including “the hit” “Agitated” (later done by the Plague.) Last but not least, Cle 3A mentioned a band called the “Dead Kennedys”, renamed the Kneecappers (remember this was in Spring 1978) featuring “Russ and Pat from Elyria”, Mr. Chris Yarmock (later Easter Monkey vocalist/sax player with Jim Jones) on vocals and Gary Lupico from WRUW and the Scene mag. – very interesting, but puzzling!

The late 70s spawned one more magazine and a bunch of bands semi-connected with it – Larry Lewis (now known for his band Faith Academy) put out a magazine called Mongoloid at a very tender age, and also had a band called Medusa Cranks. A band prominently featured in Mongoloid was the Lepers, who made their debut in June 1978 with songs such as “Desegregation Blues”, “Welcome to Cleveland”, “Avant-God” and “I Hate Coventry”. In late ’78 they had a single on Drome Records, “Cops”, “Coitus Interruptus”, “Light Up a Pack” and “Flipout”. These mid-period punk bands were probably more involved with real politics than the HC bands now – they played benefits for causes other than their own projects. One event was “Meltdown ‘78” at CSU on November 12, 1978, a benefit for the Western Reserve Alliance and the North Shore Alert – two area “No Nukes” groups. Bernie and the Invisibles, Medusa Cranks, Public Enemy, Backdoor Men, the Lepers and the Pagans played.

And so ends the tale of the Clevo Underground – you all know what goes on now – a bigger scene doesn’t necessarily make for more harmony. Thanks to Cle, Mongoloid, and PTA Magazines for the research sources for these articles.

(Postscript – several of the musicians in this article have since passed away – RIP Stiv Bators, Gary Lupico, Jim Jones and Larry Lewis.)

© Mary Ellen Tomazic 1983

[1] Later scrutiny of the film by some Stooges buffs revealed that Stiv may not have been the one who handed Iggy the peanut butter jar, but he claimed that honor and legend till his untimely death.